Designer Genes

Introduction

Designer Genes is an exciting event for the life sciences student interested in exploring the rapidly-growing field of molecular genetics - the study of how genetic information is encoded, functionalized, and manipulated at the scale of proteins, nucleic acids, and other biological macromolecules. In the course of preparing for and competing in Designer Genes, you will be confronted with questions like how genes are structured, how cells use genes to produce proteins, how modern techniques in genetics and genomics work, and how those techniques are used. You will also learn analytical skills required to interpret results of classical and modern genetics experiments. More than anything, I hope that this event inspires you to learn more about molecular genetics - a field that will continue to make the news throughout our lifetimes!

How to study for the exam - Preparation

Sometimes, it’s easy to get carried away studying for life sciences events. This is mostly due to the fact that the life sciences are very deep, and any one life sciences event can only scratch the surface of a field. (Indeed, I’ve been doing “Microbe Mission” for 8 years now - and I still don’t consider myself an expert at all!) Therefore, my colleagues and I on the Life Sciences Committee tried as best we could to summarize the content we deemed most important in the table under section 3(c) in the rules. Also note that you are responsible for the content covered in Heredity B, although you probably won’t be tested on classical genetics nearly as much as molecular genetics. As you can see, the rules are split into two main sections - Regional/State topics and Nationals-only topics. Most Science Olympiad competitors attend Regionals and States, but not Nationals, so that is the audience I will target in my discussion of the rules.

On slightly deeper inspection you’ll notice that, as promised, most of the topics center around a few fundamental themes: (1)

To discuss:

- Setting up a reference sheet

- How to split the material between event partners

What to expect during the test - During the competition

Designer Genes questions chiefly come in two flavors: Those that ask you to recall information, and those that ask you to analyze data or a situation. Tackling the former is simply a matter of knowing as much of the fundamentals of molecular genetics as possible. The latter is somewhat trickier.

Although I won’t be able to address every single problem you might face in your time as a Designer Genes competitor, I can give you a few pointers, outlined below:

-

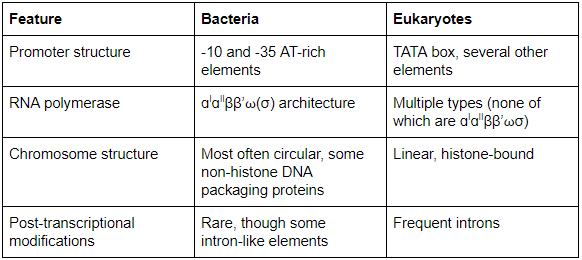

Remember the organism being asked about in the question. While eukaryotes and bacteria, the two domains of concern in Designer Genes, are alike in many ways (at the most fundamental level, both code genetic information on DNA), they do have several key differences (for example, the structure of bacterial and eukaryotic genes is quite different). Knowing the difference between the two can be a matter of getting a question totally right or totally wrong. Some key differences between eukaryotic and bacterial molecular genetics are summarized below (I’ll leave it to you to figure out precisely what all of the items below actually mean), but as you study for the event, I encourage you to make a table of your own:

-

Ask yourself, “in light of what I know about biology, does my idea make sense?” There’s no better time to ask yourself this question than while designing or evaluating an experiment. For example, let’s say you want to design an experiment to explore genes essential for DNA replication in bacteria. Is it possible to delete all copies of DNA polymerase III, the enzyme responsible for DNA replication in bacteria? What would the consequences be if you tried to delete such a gene?

-

Double, triple, quadruple check any DNA/RNA/amino acid sequence you write out by hand. Errors in handwriting a sequence most often occur when writing the reverse complement. (For example, given a DNA sequence 5’-ATCGATG-3’, what is the sequence of the reverse strand, starting from the 5’ end?) Funny story, one time, I ordered some primers to carry out some of my research. For two weeks I couldn’t seem to get my polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to work. I was completely baffled - I had been doing PCR for years at that point, so why couldn’t I get the darned thing to work? I changed everything - the reaction conditions, the concentrations of each reagent, but nothing seemed to work. One day, I looked back at the primers I had ordered. Primers, as you will discover, must be the reverse complement of the strand you intend to amplify from. It turned out that in a moment of bone-headedness, I had written down the sequence I intended to amplify from, not the reverse complement - which is what I should have written down. Two weeks down the drain, all because I hadn’t checked my work!

About the author

Colin Barber is a microbiologist at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a member of the Science Olympiad Life Sciences Committee and co-wrote the rules for Designer Genes and Heredity. You may contact him at cbarber@berkeley.edu if you have questions about Designer Genes or just want to talk science!